Computational Proximity

The goal of the computer industry has been to make computers more accessible. Largely they have succeeded, more people have computers now than at any other point in history, and more individuals have access to smartphones then ever before. The wonderful thing about this access is that anybody with a connection can look the same content. We have made the content accessible, and the computers closer to everyone, but we have failed to allow users to manipulate their own data.

Despite the strong movement to get people interested in coding, not everyone is a programmer or wants to become one. We can’t let those people languish behind without the tools needed to understand the world. The problem is not that these people don’t understand logic or mathematics, its that the machine is not representing itself to them in a manner that makes sense to them. Ideally the model the machine makes and shows the viewer would match 1:1 with the model the user has in their own heads.

Light on the Other Side

Despite how difficult the problem is, I’m quite excited to see what we come up with. Computer Science is a very new field, and we’ve barely scratched the surface of what computation looks like. We understand very little, and when that is true we have lots of possibilities.

Programming Paradigms

Gerald Jay Sussman says we really have no idea what we’re doing in We have no idea how to compute, I tend to agree with him. The dominant way of programming is the imperative style, in which you tell the computer what to do, step by step. This is not a good place to be. The more we focus on telling the computer what to do, the more we get wrapped up in the details.

The primary unit of abstraction in imperative programming is functions and objects. With functions you isolate pieces of code that are reusable and generic, however you only really know what the function returned to you. You don’t know what other side effects the function changed, or what global variables were updated.

Objects do an excellent job of encapsulating certain ideas, and you can extend them to create new objects. But single inheritance is difficult to get right, and extremely difficult to change after the class hierarchy is decided. Objects can’t really be composed without a having to write a fair bit of boiler plate to get things to mesh inside another object.

They key thing here is that these problems are not solved, and we must consider other ways of achieving these goals. We have to work further away from the metal.

The Legendary Marvin Minsky has an excellent quotation on memory management that seems applicable here:

In an ordinary programming language, like FORTRAN or BASIC, you have to do a lot of hard things to get the program even started—and sometimes it’s impossible to do these things. You must state in advance that in the computer memory certain locations are going to be used for certain specific things. You have to know in advance that it is going to use, say, two hundred storage cells in its memory. A typical program is made up of a lot of different processes, and in ordinary programs you must say in advance how each of these processes is to get the information from the others and where it is to store it. These are called declarations and storage allocations. Therefore, the programmer must know in advance what processes there will be. So you can’t get a FORTRAN program to do something that is essentially new. If you don’t know in advance what the program will do, you can’t make storage allocations for it.

We need our programs to be flexible, the biggest cost in computing is programming time, refactoring code and changing how everything operates. Those challenges exist and are made difficult because we build in assumptions into our programs. The assumptions give us performance increases, we can fit more things in less memory, or generally make things more performant. These aren’t really the problems that are important any more, we have more than enough memory, clock cycles, and the cost of these components as dropped dramatically.

We need to consider other ways to represent our programs, in other words, we need to find new ways to think, the more flexible those representations are the better off we will be.

The 60s and 70s for computer science was filled with wild and wonderful ideas. Bret Victor talks about them in his talk at dbx called The Future of Programming. Those decades created the Actor Model, Constraint / Goal Programming, Object Oriented Programming, and systems like Planner and Sketchpad. Now some of these ideas have taken root - OOP - while others have languished. Most people seem to consider how we program to be a solved problem. It isn’t and we still don’t know what we’re doing. Victor argues that that treating programming as a solved problem, and not considering other ways of doing things is the most dangerous proposition to computer science as a field. We must continue to question our assumptions in order to arrive at better solutions.

Computation is cheap

Most of the bedrock upon which our computing systems are based was developed in the 70s and 80s. The same restrictions no longer apply.

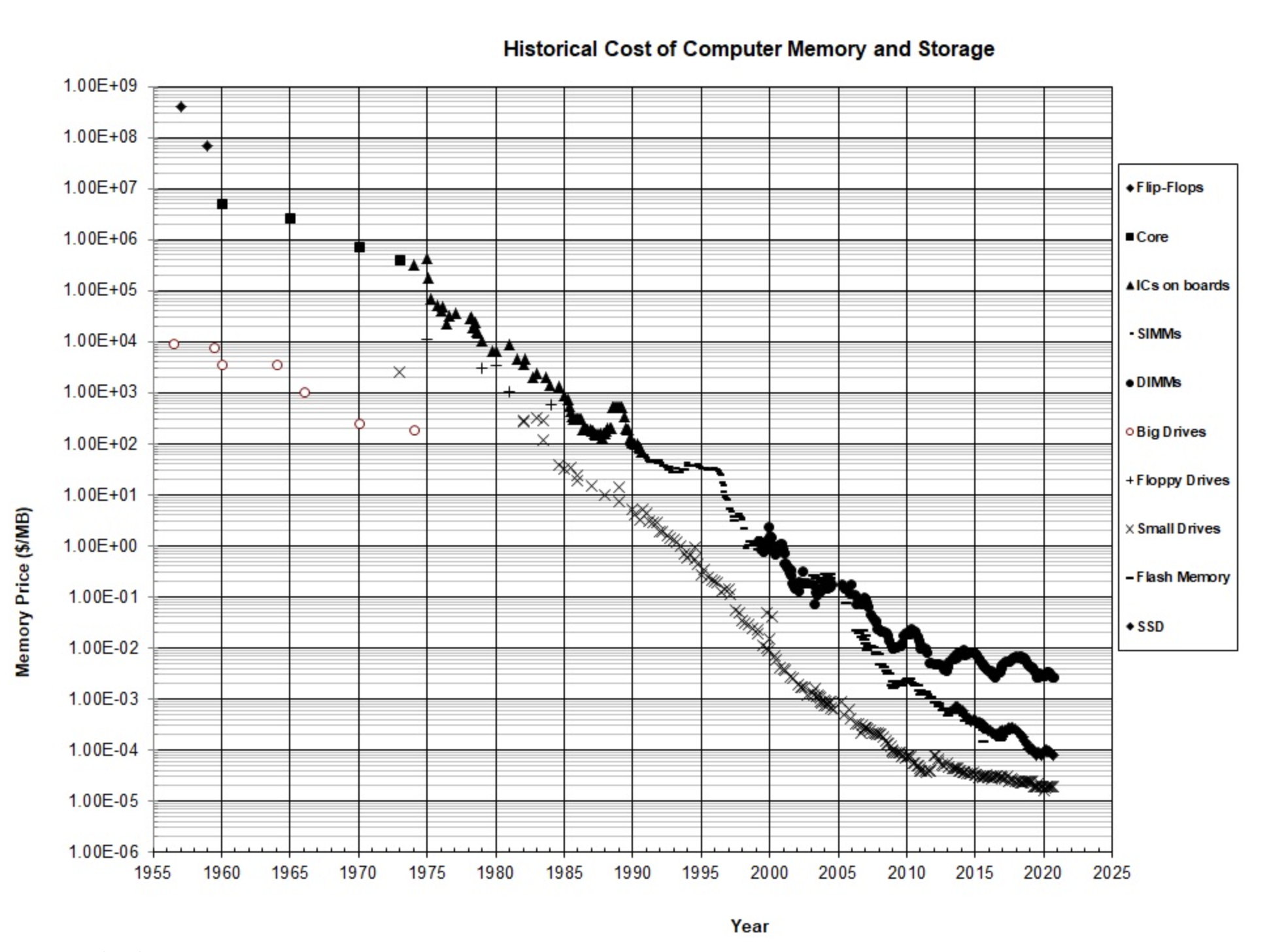

John McCallum - Graph of Memory Prices Decreasing with Time (1957-2015)

With virtual memory we don’t have to worry about having enough space on disk, we don’t have to worry about where exactly things are allocated, and the same overhead that was considered to be unconscionable we can now consider.

Take SketchPad for example, was developed in 1963 by Ivan Sutherland. Written for a Lincoln TX-2 - a computer the size of a room - Sketchpad is still one of the most powerful and comprehensive logical sketching systems. At the time, Sketchpad was an extremely intensive program to run, now a standard laptop could handle Sketchpad easily. Yet we don’t have programs that are nearly as powerful editors for images.

My point is that we now can afford to spend more CPU cycles but our apps are not getting any more powerful. Why is this?

In part the amount of data we’re dealing with has ballooned astronomically. Our focus then shifts to working with larger images, or larger videos while letting the ways we manipulate them stagnate. For these areas this result makes a great deal of sense.

But there are other areas in which we ought to be able to do more but haven’t. Take creating any sort of interactive system, eg a simple game or animation. Those tasks are still incredibly hard. Solving those issues are immensely difficult, but there are areas in which we can give the user more power at very little cost. One of these opportunities is to make computation more accessible.

Decreasing Computational Proximity

We need to open up the hood and allow for users to have more flexible interactions. This doesn’t mean that everyone who uses a computer should have to program, but rather that they should be able to model what they’re doing using flexible composable commands.