Group B Rally

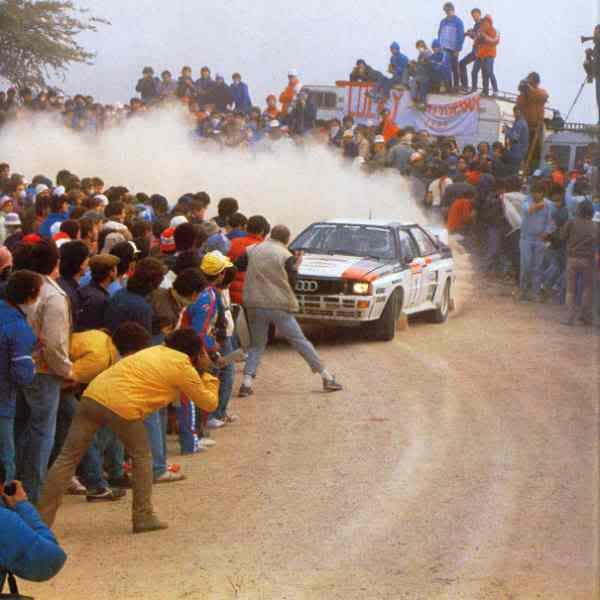

Taken during the height of the Group B Rally craze, this photograph shows the true nature of the sport. Walter Röhrl, the two-time world champion, commanding his 350 BHP Audi A2 Quattro through the bends of the Italian Countryside, is truly the epitome of rally. Inside the aluminum roll cage, surrounded by safety gear and spare parts, sit two men wedged into bucket seats and 6-point harnesses. Despite the heat, they wear woolen fire retardant polymer suits; despite the lack of air conditioning, they wear full crash helmets with woolen fire masks underneath. This is no game for mere mortals.

Flying through the segments, at the very limit of what is physically possible; these drivers aren't in the game of close enough; they're in a game with no limitations except themselves, the man next to them and the 350 BHP Audi A2 Quattro beneath them. It's not about the titles for them, it's not about the glory or the money. It's about the risk, it's about pushing the envelope and doing the best they possibly can. If they wanted to be famous, or rich, they would've become an actor or a businessman, but instead they chose to be a driver and not just any driver, but a rally driver.

They don't know what's around the next corner until their co-driver calls out 4L or 150 1R. 4L being a left-hand turn at a near right angle and 1R being a hairpin right turn in 100 yards. They trust and rely upon each other; the co-driver trusts that the driver heard his calls and the driver trusts that the calls he heard were accurate. In normal racing, you're on a closed circuit with marshals and an on-site hospital, with Rally you have none of those amenities. This is the case in the Paris-Dakar Rally, and many others, which spans over 3726 miles in the North African sun. At any given point, you could be hundreds of miles from the nearest competitor, and even further from the nearest town. Group B, however, was not known for these sorts of races, although they certainly participated, Group B is the 80s equivalent of the World Rally Championship. Spanning over multiple continents including South America, Europe, North America and Africa. The Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile (FISA) created a multitude of different classes of rally vehicles. Group B was considered the experimental group with no restrictions. It lasted 3 years, from 1986 to 1989.

Group B is considered by motoring enthusiasts to be the golden age of rally. Less than 75 models, including prototypes, were produced for use in Group B. All of them trying to win back the advantage in new ways and new technology, Audi created 4WD, labeled QUATTRO, for use in Rally, and later Peugeot introduced balanced mid engine automobiles in the form of its Peugeot 205 T16. With these advancements, factory teams, those who are linked to a large automotive manufacturer pushed the envelope even further in order to sell more automobiles. This pressure from the factory forced some of the less safety-conscious decisions that were made in Group B, Such as Lancia mounting the fuel tank in its S4 beneath the pilots' seats in order to attain a lower center of gravity.

Henri Toivonen and his navigator Sergio Cresto were killed when he lost control of his Lancia S4 and veered off the side of a cliff. If the fall did not kill them then the fire billowing around them did. The danger of Group B Rally is readily apparent, yet despite similar accidents before Toivonen's death the racing would not be stopped.

When walking through New York City there are always those people. Their noses a mere inch from a semi-truck barreling past, their feet centimeters from a passing cab. They try to cross the street as quickly as they can as if the first one to reach the other side or get closest to a passing car is the most experienced New Yorker, or as if some prize awaits them. They do it because it's tedious to stand on the curb, perhaps it's a sense of thrill; standing out in the street as cars whiz past. Group B Rally was full of these sorts of people.

Part of the appeal is the risk involved; the sheer rock faces, the hairpin turns and trees lining the road. We, as a society, have created these even, paved, and over engineered roads that dull our sense of adventure. We yearn for something more unexpected, more primal and adventurous. It's exactly our advancements that force this change; the further we progress the more we want the past. No more automatic braking systems, no more Drag Reduction System and no more overly complex systems that make things easier and more predictable.

They do it to give death the bird. Staring death in the eye and saying "not this time buddy". There's some innate beauty with coming so close to the end, you start to appreciate what you have. That engine note seems just a little bit sweeter, the shifts a little cleaner and the steering more precise. Despite being so close, they're still in control, they're still defying nature and they're enjoying every second of it.

The people we look up to and honor always operate in a world we can't comprehend. The stuff of legend is that of the unknown, how do they manage to drift around hairpins at 50 MPH or fly over dirt crests at 150 MPH. We simply don't know, it's so far out of our realm of speed limits and structure that it attracts us like flies on honey. Despite knowing how they achieve it mechanically, (traction control or 4WD) we still cannot fathom how they actually achieve these feats in a practical sense. It's still far out of our realm of comprehension, the world of automatic transmissions, 30MPH roads and taking turns at 15MPH.

These drivers are now rally legend, yet back in the heyday of Group B teams would hire full teams of professionals to ensure that the drivers were in perfect condition for the stages ahead. They used techniques such as acupuncture, full body massages and prescription drug supplements to keep the drivers in ideal form for the races. The Paris – Dakar, one of the longest rallies in the world, required multiple weeks of driving on some of the most treacherous roads in the world along with extreme speed in order to be victorious. In order to win their suspensions were firm, in order to become a champion they minimized breaks, in order to be successes nothing short of superhuman was allowed. With the factory team stakes so high, the teams were always looking for means of improvement, not just limited to the vehicle but also the driver and co-drivers stamina and peak operating window.

These stages are lined with people; in the mid 1980s Group B was one of the most popular forms of motor racing. Why do they dart out of the way as the 350 BHP Audi A2 Quattro roars past and they immediately fill in the gaps? As these colossi roar, growl and snarl through the masses they have a sense of vicariousness. Instead of staying home, watching history being made, or reading about past history, they get to be part of history. Part of something unique and different from anything the world had seen up to that point. We all line up for something new, we value that of which we can't attain or is difficult to attain. The closer they are to these behemoths the closer they are to their dreams and aspirations of being guy in the aluminum roll cage, surrounded by safety gear and spare parts, wedged into bucket seats and 6 point harnesses; the guy who is drifting around those hairpins at 50+ or bounding through the countryside at 150 MPH.

The biggest problem with Group B was its popularity. FISA did not have the proper crowd management techniques in place at each of the stages; today you have a marshal every 100 yards without exception, but in the height of the Group B craze it was immeasurably more difficult to keep back thousands of spectators all vying for a chance to get as close to their idols as they can. The spectators are not all at fault, as a good portion of the accidents occurred at stages with few spectators (such as cliff side service roads or other inaccessible areas). A combination of its increased spectators and a strong desire for rally wins fueled by factory teams sales seems to be the true cause of the madness that was Group B.

Unfortunately, FISA was unable to make the proper regulation changes before the horrific incidents that occurred within Group B transpired. Over the course of those 3 years, FISA made no changes to the structure of Group B. The key to allowing Group B to survive is in more regulation on the spectators, such as how close they can stand to vehicles, as well as rally stages that are far shorter in length.

People are always racing. You start with being the first across the street, and maybe you stop there. Others take it a little further and a little further more and before you know it you're standing in an access road in rural Italy staring down a 350 BHP Audi Quattro A2. You see it coming, you know it's there, but you wait. You know when to move, at the last second you leap out of the way and it charges past. When the next one comes you'll get even closer, always pushing the envelope because you know where the limit lies.