Design Principles Behind Smalltalk

Ingalls describes Smalltalk, a language that "Provides Computer support for the create spirit in everyone". Smalltalk is a language, just as Spanish, German or English are languages. The goal of this language, and all others, is to send a model from one individual to another. In order to do so they have to have the same initial assumptions. That is they both speak the same language, and have similar linguistic concepts to work of off.

Implicit and Explicit Communication

Somewhat famously this is Licklider's Intergalactic Computer Network problem. Licklider questions “how do you get communications started among totally uncorrelated “sapient” beings?” Licklider and Ingalls are talking about the same fundamental idea of transmitting a model from one entity to another. It's interesting to note how often this communication problem pops up in different contexts, the same issue is present in mathematics where different notation means different things in different fields, or philosophy where terms mean something to a different group and an entirely different thing to another. These groups need a shared language in order to collaborate.

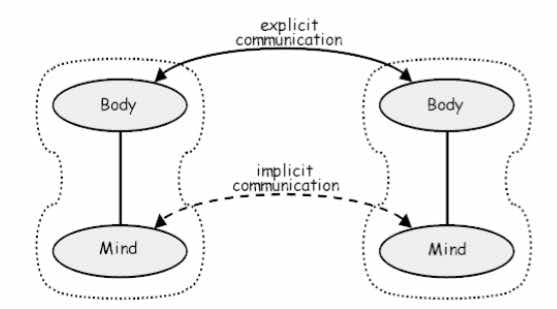

Ingalls notices that it does not matter if the model is being transmitted from person to person, machine to machine or from person to machine or vice versa. There is a certain amount of fundamental knowledge required to transmit a model and have it be understood in the manner it was intend. Ingalls terms this initial knowledge to be implicit communication, and the model itself as explicit communication.

Figure 1, Design Principles Behind Smalltalk

Figure 1, Design Principles Behind Smalltalk

Most of human language is built upon the implicit communication, in fact Ingalls notes that "Human language is built upon allusion". Part of the work I've been doing with Blaze, is about how we get the same model in the computer as we have in our own heads. Smalltalk acknowledging this distinction sets itself apart from other languages at the time.

Object Oriented Programming

One of the legacies from the Smalltalk system is Object Oriented Programming (OOP). Steve Jobs does an excellent job of explaining OOP with the following from Rolling Stone's 1994 Interview of Jobs:

Objects are like people. They're living, breathing things that have knowledge inside them about how to do things and have memory inside them so they can remember things. And rather than interacting with them at a very low level, you interact with them at a very high level of abstraction, like we're doing right here.

Here's an example: If I'm your laundry object, you can give me your dirty clothes and send me a message that says, "Can you get my clothes laundered, please." I happen to know where the best laundry place in San Francisco is. And I speak English, and I have dollars in my pockets. So I go out and hail a taxicab and tell the driver to take me to this place in San Francisco. I go get your clothes laundered, I jump back in the cab, I get back here. I give you your clean clothes and say, "Here are your clean clothes."

You have no idea how I did that. You have no knowledge of the laundry place. Maybe you speak French, and you can't even hail a taxi. You can't pay for one, you don't have dollars in your pocket. Yet I knew how to do all of that. And you didn't have to know any of it. All that complexity was hidden inside of me, and we were able to interact at a very high level of abstraction. That's what objects are. They encapsulate complexity, and the interfaces to that complexity are high level.

Guy Steele talks about how Java embodied similar ideas in Growing a language at the 1998 OOPSLA Conference. Steele begins by limiting his vocabulary to primitives. For Steele primitives are words with one syllable. From these primitives he builds more complex words, to talk about the evolution of java. Steele has to set the implicit state of the language explicitly, and build up the shared model of the world.

OOP is a great way to think about programs and abstract away complexity. But it has fallen short of the goals smalltalk has laid out. While it is true that we think about things in terms of objects in the actual world, the systems the computer knows about have not been built in a manner that is intuitive to us. For the object model to be entirely useful to us we must have objects that behave in similar ways to the way normal objects behave. The issue is building up the shared implicit models to facilitate this communication.

Programming languages are not meant to be learned, they're supposed to be implemented. This seems to be a fatal flaw when it comes to a system that can build up shared representations and make meaningful use of the objects it knows about.

Smalltalk's Ambitions

When Smalltalk first arrived in 1972, OOP was an entirely new way to look at the world. Ingalls goes on to explain the role of Smalltalk beyond just a normal programming language:

This fact is responsible for the difficulty of explaining Smalltalk to people who view computer languages in a more restricted sense. Smalltalk is not simply a better way of organizing procedures or a different technique for storage management. It is not just an extensible hierarchy of data types, or a graphical user interface. It is all of these things and anything else that is needed to support the interactions shown in figure 1.

Smalltalk's "extensible hierarchy of data types" or OOP isn't really the point, the point is to allow the user to think in a manner that is natural to them. The key concept being that the tools are made to fit the user, not the other way round. Surprisingly enough we haven't made a lot of progress on this point. We have made excellent progress with OOP, but the user and the computer still lack a shared implicit model of the world.

We have a lot of initiatives to help people learn to code. Year of Code, Code.org, Yes we Code as well as videos declaring computer science the new literacy. I don't think these initiatives are a bad thing, but we would be more successful if we acknowledged that computers have different intuitions from us. They fundamentally think in a radically different and bizarre way to most of us. Smalltalk has shown us the way, we have to create systems that have shared implicit models with their users, and allow them to communicate with a user easily. Despite this, there seems to be a focus on moulding the user to the programming language, and thats a shame.

It's a shame because it alienates people from technology, and creates a hard line between those who are able to code and those who cannot. The emphasis is on thinking about efficiency and algorithms for image manipulation or audio compression, which are without a doubt important tasks.

Yet very few people will care to implement their own compression system, and Open Source Libraries are good enough for most tasks. The vast majority of time is spent combatting incidental complexity, and therefore writing simple systems and code is 10x more important than small increases in efficiency.

The more adaptable the system, the empowering it is. If they can transmit the model in their heads, to a model in the machine, there would be no bounds in what man and machine can achieve together.